This report is for sharing lessons and experiences from advocacy on land rights for wider reflection within the ACT Alliance network and other civil society organisations. It is based on valuable input received during a workshop held on 18 October 2017 in Brussels that was organised by the ACT Alliance EU Working Group on Food Security. It brought together Brussels-based NGOs who support vulnerable communities in their fight against land-based investments and business activities which threaten their legitimate use of land, forests and fishing waters.

Executive Summary

Insecure land tenure is threatening the livelihoods of many vulnerable communities across Africa, Asia and Latin America. Across large areas of Africa, for example, the land communities are using to grow food, make a living or for cultural purposes is governed by customary tenure systems. As a result, their land use is often undocumented or even unrecognised, and hence unprotected by the formal legal system.

In many customary tenure systems, unequal power relations mean that traditional leaders can sell or lease the land used by local households to outsiders against their wishes. Women who depend on land for their food, livelihoods and cultural expression are most vulnerable, given that they have far fewer of the albeit limited land rights enjoyed by men in these rural agrarian societies.

For these reasons, securing the land rights of vulnerable communities has been a long-standing advocacy priority of ACT Alliance EU (ACT EU) member organisations. Many ACT EU members support community and civil society-led actions in developing countries to secure the land rights of vulnerable and indigenous communities. This is also why ACT EU has prioritised this as a key issue in its advocacy targeting EU institutions.

To gain a better understanding of how EU institutions can better protect community land rights, the ACT EU working group on food security organised a one-day workshop in October 2017. It brought together Brussels-based INGOs who support vulnerable communities in their fight against land-based investments and business activities which threaten their legitimate use of land, forests and fishing waters.

Drivers of global land rush at EU level

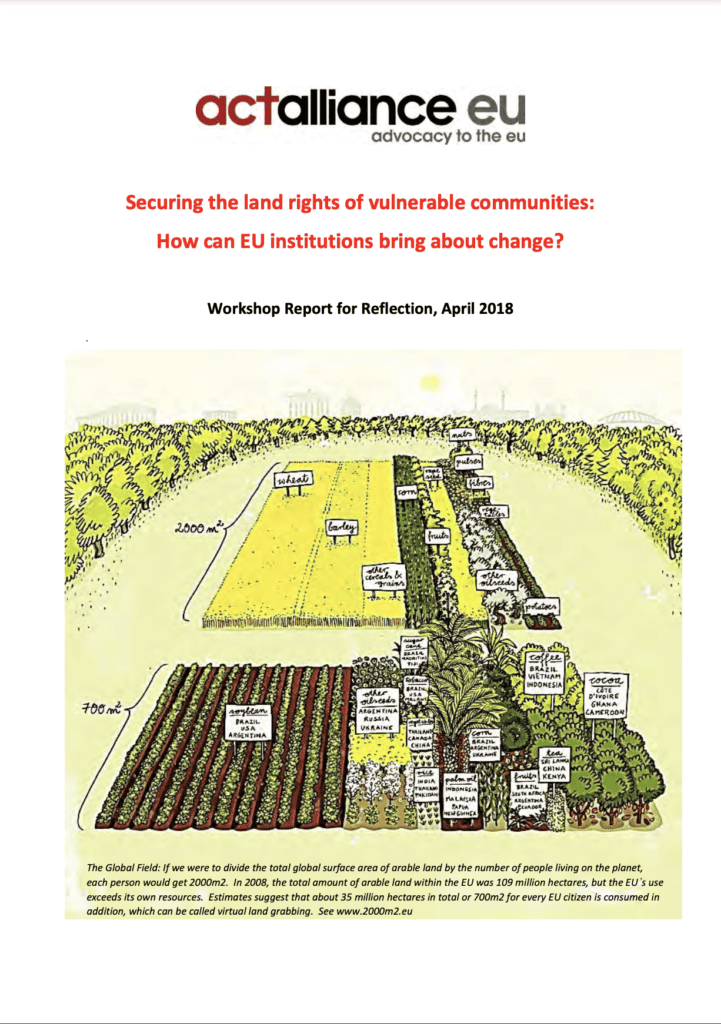

Drivers of global land rush are not just sitting in faraway countries. They are part of the decision-making processes in EU institutions. The pursuit of unlimited growth, the production and consumption patterns of us as affluent European societies, the un-appeased hunger for energy, rent-seeking investment funds and pension schemes, where we put our savings are turning into drivers of land use changes. A big part of governance responsibility for private and public finance, or for trade and investment policies lies at the EU level.

Furthermore, our European consumption and production patterns (SDG 12) impact in many ways on imports and exports that rely on land and natural resources here and abroad and are governed and regulated by EU institutions.

The dominant growth model leads to land use changes and directly or indirectly to the depletion of natural resources, land and water grabs, loss of biodiversity, and concentration in the seed and farming sector. The ‘sacrifices’ for the growth paradigm are huge; they include curbing policy space and subordinating the Right to Development to narrow and unsustainable pathways.

Often, aid conditionality and foreign investment come along with market-based land reforms, changes to seed laws, trade liberalisation and market opening for the private sector from abroad. Currently, EU public and private finance is subject to various kinds of due diligence and accountability mechanisms which mostly fail to safeguard effectively against land (and water) grabs.

European food, agricultural and trade policies propose ‘climate smart’ and technological fixes as solutions to meet Paris Agreement ambitions, while they continue to avoid taking full responsibility for our own excessive consumption of food, feed, fibre, fuel and production models.

The EU’s response to global climate change and planetary resource depletion relies on models such as, for example, Agriculture 2.0 (push for digitalisation and big data), Bioeconomy (access to biomass and agricultural raw materials such as palm oil, soy, sugar, timber), Industry 4.0 (new biotechnology and geoengineering in agricultural production); all geared towards maintaining the EU’s competitiveness and accessing new markets. This again, will impact global land use and livelihoods security.

Another response is the global CSO campaign for a UN treaty on business concerning human rights, which should have primacy over trade and investment agreements. Likewise, the Right to Food movement works towards binding Tenure Guidelines on Land, Fisheries and Forests, and the adoption of the new UN Declaration on Peasant Rights. All of these are based on efforts towards realising the right to food based on approaches towards more food sovereignty and agroecological practices.

How can EU institutions bring about change?

At the Brussels level, some gains are made in EU legislation on the sector or product-specific regulations that may be used as precedents (illegal timber, illegal fishing, conflict minerals, sustainable finance, etc) to enhance and insert binding and enforceable human rights provisions and due diligence into new or reviewed EU legislation. The objective is to push for commitments under EU human rights policies to deliver new procedural rights for CSOs, access to justice and remedies for affected communities.

Most Brussels-based INGOs work already within CSO coalitions to strengthen impact, share competence and amplify outreach of specific land struggles, pushing for a change in EU regulation as pressure points and leverage to prevent, halt or reverse land grabs.